A Struggle for a Living Wage

Key Takeaways

- The National Education Association this week released the Education Support Professional Earnings Report, which offers a breakdown of ESP pay in K-12 and higher education.

According to a 2021 National Education Association survey of its members, 37 percent of PK-12 education support professionals (ESP) work two or more jobs. A little more than a third work their extra job(s) inside the school system. Twenty-eight percent have a permanent position outside of education, and 29 percent have a temporary position outside of education.

While some call it moonlighting or a side hustle, for too many educators across the nation working a second, sometimes a third job, is just doing what is necessary to make ends meet. Chronic low pay for ESPs, who include school bus drivers, food service professionals, paraeducators, custodial and maintenance staff and more, is one of the main contributors—along with lack of respect, inclusion, and crushing workloads—behind the widespread staff shortages that have hit school districts across the nation.

“For decades, America’s educators have been chronically underappreciated and shamefully underpaid,” said NEA President Becky Pringle. “Throughout this persistent and ongoing pandemic, they have demonstrated their commitment to all students. After persevering through the hardest school years in recent memory, our educators are exhausted and feeling less and less optimistic about their futures."

The State of ESP Pay

"Our bus drivers are struggling to start with,” says Henry Sanchez, a bus driver from Michigan. “The pay isn’t good enough to keep people or hire new drivers. If you have a job that keeps you in poverty, it’s not a good job."

“Many ESPs have to work more than one job, and you can’t be tired working with students,” adds Margaret Powell, a data manager in Wake County, North Carolina. Powell's 17-year-old son makes more per hour at McDonald's after five months than many ESPs make after years on the job.

After the gains generated by the #RedForEd movement in 2018-19, educator pay across the nation has stagnated . That's according to new salary/earnings reports released by NEA this week. For the first time this year, in addition to the Teacher Salary Benchmark Report and Rankings and Estimates, NEA also released the ESP Earnings Report, which offers a breakdown of ESP pay in K-12 and higher education.

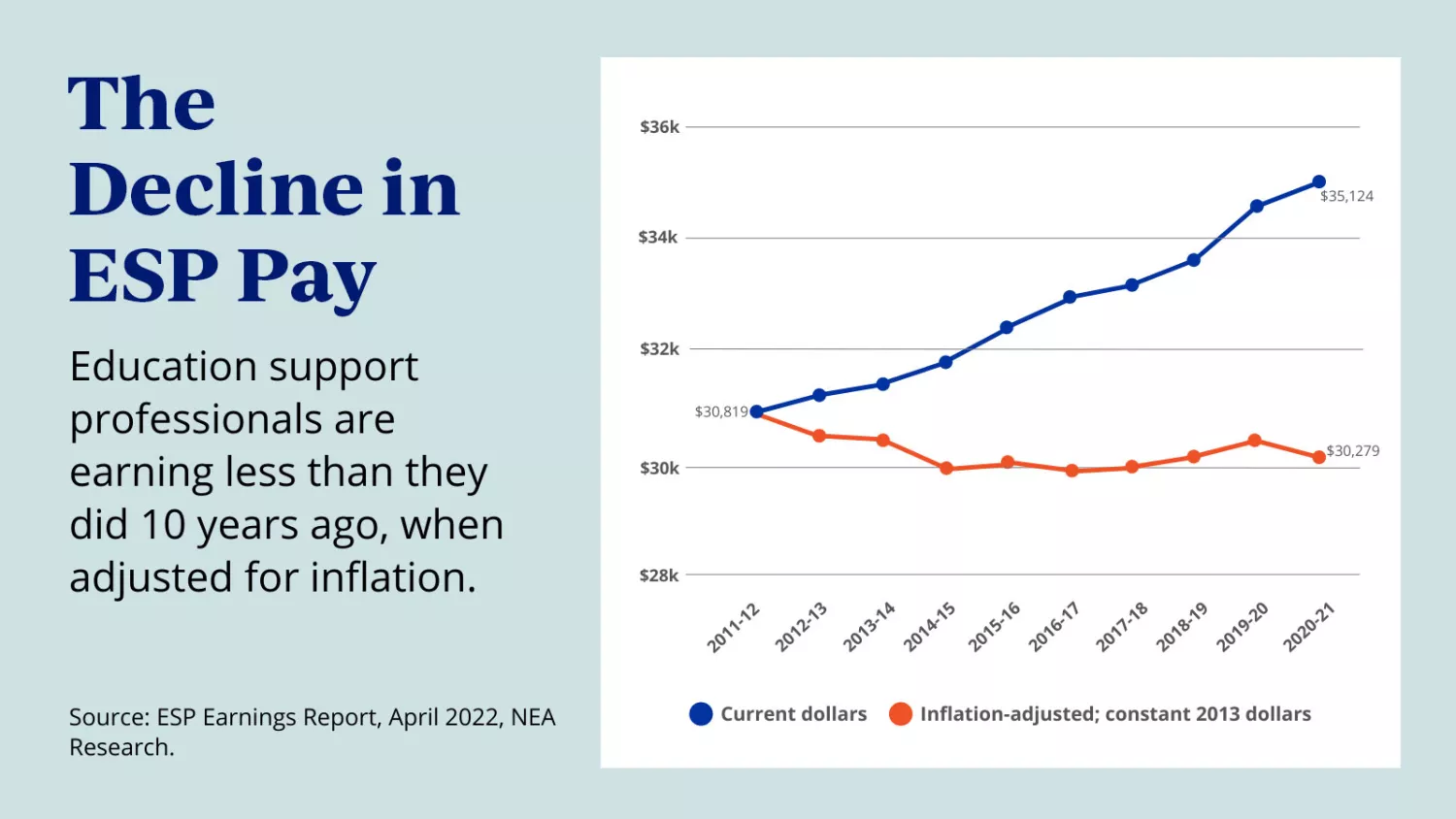

The NEA data reveals that in all school job categories, pay is lower now than it was in 2012, when adjusted for inflation. The nearly 2.9 million ESPs working in public education are no exception.

The average salary for ESPs working full-time (more than three-quarters of all ESPs) rose from $30,819 in 2011-12 to $35,124 in 2020-21. However, when adjusted for inflation, the earnings for ESP in 2012 dollars have actually declined from $30,819 to $30,279.

K-12 ESPs (75% of the ESP workforce) who work full-time earned an average $32,837, while higher education ESPs (25% of the workforce) who work full-time earned an average $44,225.

The report also found that 13.7 percent of full-time K-12 ESPs earned less than $15,000, and 27.8 percent earned between $15,000 and $24,999. Within higher education, 17.4 percent earned less than $25,000, and 7.5 percent earned less than $15,000.

Overall, across the U.S., the average salary paid to ESPs is at least $10,000 below a basic living wage in every state but one (Maryland).

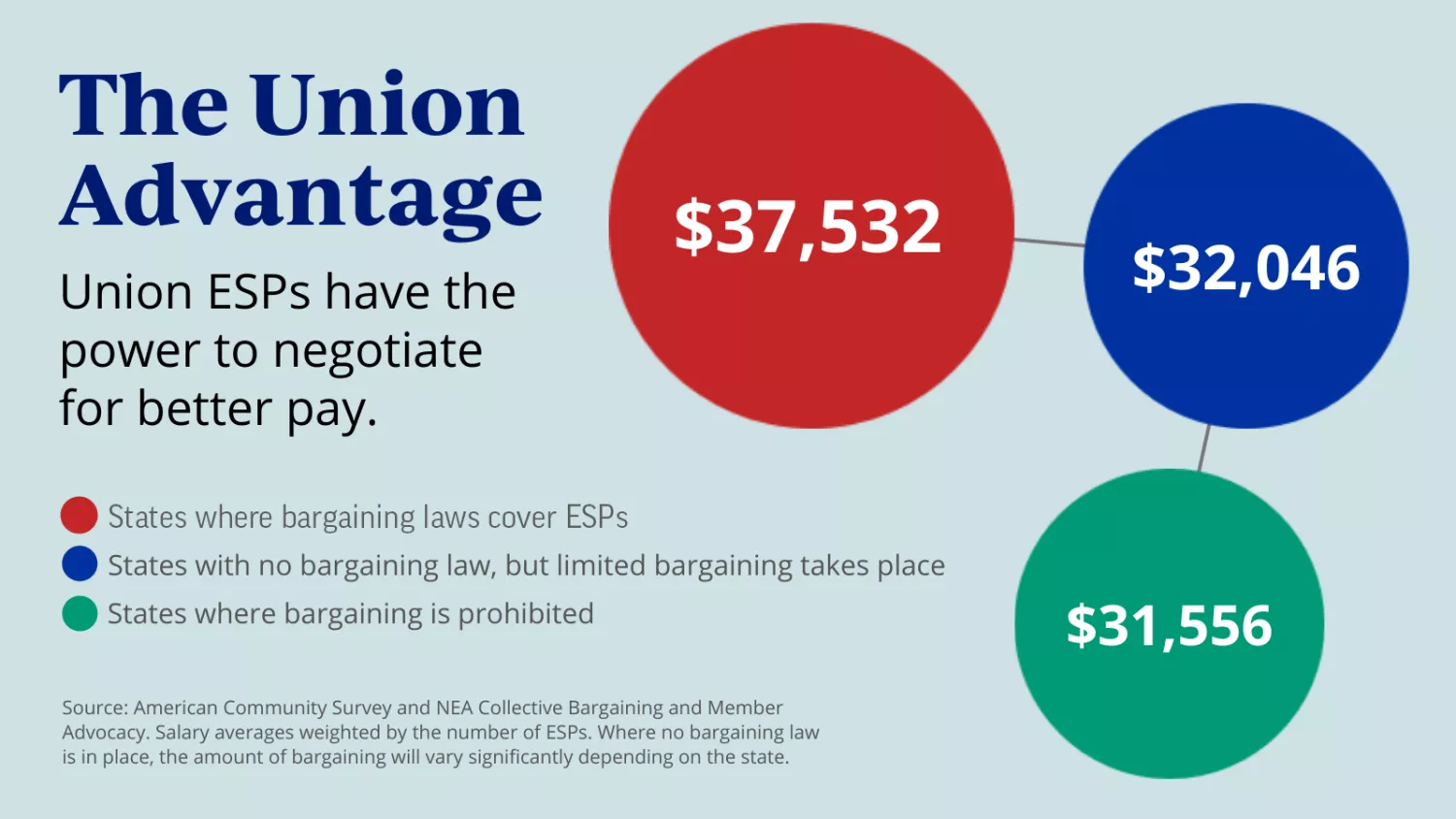

Despite the sobering news, encouraging signs can be found in collective bargaining, according to the report. ESPs in states with collective bargaining statutes earn almost $6,000 more a year, on average, than those in states where collective bargaining is prohibited.

In 2022, union power has also been on display in the halls of state capitols.

In March, New Mexico lawmakers approved a bill that guarantee a 7 percent raise for all school employees. A few weeks later in Mississippi, educator advocacy helped secure the passage of a bill providing the largest pay increase the state’s teachers and teaching assistants have ever seen. And last week, Alabama educators celebrated the passage of the largest education budget in state history, which includes a pay increase for all public education employees and goes into effect on October 1.

"If we want to reverse course and keep qualified teachers in the classroom and caring professionals in schools," said Pringle, "then we must increase educator pay across the board and expand access to collective bargaining and union membership for all those working in public education."

Educator Pay in Your State

-

Alabama

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$41,974NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#24in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$55,834State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#33in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

69¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$48,111Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$11,827Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#41in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$28,708Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#41in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$42,427Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#29in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$86,762Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#34in the nation -

Alaska

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$50,203NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#5in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$74,167State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#10in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

83¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$63,956Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$20,286Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#7in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$42,241Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#3in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$45,754Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#16in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$84,063Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#38in the nation -

Arizona

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$41,496NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#27in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$56,775State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#32in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

67¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$52,528Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$10,186Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#49in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$29,079Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#40in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$43,969Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#22in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$99,098Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#15in the nation -

Arkansas

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$37,168NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#48in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$52,610State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#46in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

76¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$44,463Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$11,856Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#40in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$28,050Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#44in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$37,306Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#48in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$74,163Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#49in the nation -

California

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$51,600NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#4in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$88,508State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#3in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

81¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$54,070Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$16,423Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#18in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$39,321Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#7in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$51,089Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#3in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$121,071Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#1in the nation -

Colorado

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$37,124NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#49in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$60,130State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#25in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

63¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$53,043Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$14,089Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#28in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$32,574Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#22in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$44,753Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#19in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$92,181Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#26in the nation -

Connecticut

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$48,007NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#9in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$81,185State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#6in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

82¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$63,303Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$23,601Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#5in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$39,502Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#6in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$52,327Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#2in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$109,530Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#5in the nation -

Delaware

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$44,037NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#17in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$65,647State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#15in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

88¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$59,978Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$18,331Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#15in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$43,543Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#2in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$40,645Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#37in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$116,394Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#3in the nation -

Florida

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$45,171NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#16in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$51,230State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#48in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

80¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$49,625Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$11,584Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#43in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$31,286Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 202#27in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$40,459Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#38in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$100,126Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#13in the nation -

Georgia

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$38,926NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#41in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$62,240State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#21in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

72¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$47,638Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$13,537Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#30in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$29,616Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#35in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$39,672Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#40in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$84,655Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#36in the nation -

Hawaii

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$50,123NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#6in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$67,000State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#14in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

86¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$82,158Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$19,211Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#12in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earning

$38,984Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#8in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$46,590Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#12in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$110,204Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#4in the nation -

Idaho

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$40,394NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#30in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$54,232State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#42in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

74¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$49,343Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$9,046Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#51in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$26,681Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#49in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$35,658Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#50in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$78,392Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#45in the nation -

Illinois

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$42,213NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#23in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$72,315State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#12in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

76¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$52,809Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$19,890Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#8in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$34,814Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#14in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$44,356Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#21in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$97,392Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#17in the nation -

Indiana

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$40,959NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#29in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$54,596State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#39in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

78¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$50,562Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$11,909Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#39in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$29,574Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#37in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$41,444Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#32in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$93,107Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#25in the nation -

Iowa

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$39,208NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#36in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$59,581State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#27in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

83¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$51,875Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$12,855Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#34in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$29,928Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#32in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$47,043Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#10in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$101,207Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#11in the nation -

Kansas

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$40,130NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#34in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$54,988State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#35in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

76¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$52,793Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$13,805Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#29in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$26,705Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#47in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$40,152Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#39in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$83,153Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#39in the nation -

Kentucky

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$38,010NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#44in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$54,574State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#40in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

76¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$49,324Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$13,268Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#31in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$26,686Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#48in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$38,821Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#44in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$77,923Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#46in the nation -

Louisiana

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$43,270NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#19in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$54,097State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#43in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

72¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$49,467Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$12,767Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#35in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$28,156Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#43in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$41,407Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#34in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$73,995Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#50in the nation -

Maine

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$39,101NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#37in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$58,757State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#29in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

77¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$54,307Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$18,934Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#13in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$30,856Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#28in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$38,279Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#46in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$84,209Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#37in the nation -

Maryland

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$49,451NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#8in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$75,766State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#9in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

74¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$50,383Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$16,893Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#17in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$38,755Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#9in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$45,719Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#17in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$99,713Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#14in the nation -

Massachusetts

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$49,503NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#7in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$89,538State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#2in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

79¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$61,322Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$22,712Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#6in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$37,080Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#12in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$49,041Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#4in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$102,048Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#8in the nation -

Michigan

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$38,963NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#39in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$64,884State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#16in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

79¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$47,235Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$12,924Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#33in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$30,303Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#31in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$47,666Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#8in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$104,706Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#6in the nation -

Minnesota

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$42,293NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#22in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$64,184State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#18in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

72¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$52,283Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$15,205Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#21in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$33,155Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#19in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$48,510Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#7in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$96,553Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#19in the nation -

Mississippi

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$37,729NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#45in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$47,902State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#51in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

86¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$47,142Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$10,829Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#47in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$25,826Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#51in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$34,898Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#51in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$73,096Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#51in the nation -

Missouri

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$34,052NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#50in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$52,481State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#47in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

70¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$46,944Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstituteePer Student Spending

$11,043Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#45in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$29,507Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#38in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$42,751Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#27in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$80,980Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#40in the nation -

Montana

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$33,568NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#51in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$53,628State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#44in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

82¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$53,181Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$13,202Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#32in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$29,756Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#33in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$39,318Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#41in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$79,719Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#43in the nation -

Nebraska

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$37,186NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#47in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$57,420State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#31in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

78¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$52,132Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$14,174Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#27in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$30,358Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#30in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$42,560Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#28in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$89,770Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#27in the nation -

Nevada

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$42,552NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#21in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$57,804State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#30in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

81¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$56,791Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$10,800Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#48in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$37,210Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#10in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$44,800Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#18in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$94,143Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#23in the nation -

New Hampshire

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$40,272NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#33in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$62,783State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#20in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

71¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$61,451Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$19,839Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#9in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$30,547Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#29in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$44,705Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#20in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$95,237Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#20in the nation -

New Jersey

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$55,143NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#2in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$79,045State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#7in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

92¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$64,342Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$23,890Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#4in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$40,346Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#4in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$53,200Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#1in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$121,056Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#2in the nation -

New Mexico

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$42,981NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#20in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$54,272State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#41in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

73¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$46,755Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$15,338Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#20in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$27,602Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#45in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$38,258Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#47in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$80,444Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#41in the nation -

New York

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$47,981NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#10in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$91,097State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#1in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

86¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$54,870Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$28,963Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#1in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$39,922Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#5in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$48,582Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#6in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$100,189Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#12in the nation -

North Carolina

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$37,676NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#46in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$54,863State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#36in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

74¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$48,346Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$11,627Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#42in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$29,349Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#39in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$42,338Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#30in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$87,011Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#33in the nation -

North Dakota

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$41,587NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#26in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$55,666State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#34in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

80¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$50,535Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$15,990Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#19in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$32,029Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#24in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$47,627Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#9in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$80,213Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#42in the nation -

Ohio

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$39,094NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#38in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$64,353State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#17in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

86¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$47,760Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$14,378Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#26in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$33,717Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#18in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$46,001Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#14in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$96,972Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#18in the nation -

Oklahoma

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$38,154NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#42in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$54,804State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#38in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

68¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$47,322Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$10,951Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#46in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$25,881Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#50in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$38,351Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#45in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$79,342Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#44in the nation -

Oregon

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$40,374NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#31in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$70,402State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#13in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

72¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$61,045Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$15,152Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#22in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$32,342Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#23in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$43,869Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#24in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$93,307Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#24in the nation -

Pennsylvania

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$47,827NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#11in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$73,072State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#11in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

84¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$47,690Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$19,412Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#11in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$34,716Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#15in the nationAverage HE ESP Earning

$43,899Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#23in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$101,519Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#9in the nation -

Rhode Island

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$45,337NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#15in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$76,852State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#8in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

91¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$61,322Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$19,561Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#10in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$37,114Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#11in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$45,944Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#15in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$98,997Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#16in the nation -

South Carolina

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$38,929NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#40in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$54,814State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#37in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

91¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$45,477Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$12,692Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#36in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$29,579Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#36in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$42,968Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#26in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$87,379Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#31in the nation -

South Dakota

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$41,170NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#28in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$50,592State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#49in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

83¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$51,278Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$11,408Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#44in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$28,317Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#42in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$36,805Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#49in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$75,541Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#48in the nation -

Tennessee

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$40,280NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#32in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$53,285State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#45in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

75¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$46,745Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$12,157Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#37in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$27,080Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#46in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$39,283Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#42in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$85,032Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#35in the nation -

Texas

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$45,493NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#14in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$58,887State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#28in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

77¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$43,776Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$12,060Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#38in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$29,677Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#34in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$42,282Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#31in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$94,781Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#21in the nation -

Utah

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$46,880NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#13in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$59,671State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#26in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

72¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$49,686Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$9,618Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#50in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$33,846Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#17in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$41,413Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#33in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$94,364Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#22in the nation -

Vermont

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$41,587NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#25in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$62,866State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#19in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

87¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$84,954Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$25,053Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#3in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$33,092Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#20in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$38,927Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 202#43in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$88,273Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#30in the nation -

Virginia

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$43,845NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#18in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$61,367State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#22in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

68¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$49,017Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$15,002Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#23in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$32,835Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#21in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$43,867Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#25in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$101,425Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#10in the nation -

Washington

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$52,142NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#3in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$81,510State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#5in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

72¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$52,649Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$18,162Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#16in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$36,150Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#13in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$47,022Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#11in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$103,101Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#7in the nation -

Washington, D.C.

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$56,313NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#1in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$82,523State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#4in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

81¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$78,904Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$26,786Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#2in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$43,811Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#1in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$49,035Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#5in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$87,026Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#32in the nation -

West Virginia

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$38,052NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#43in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$50,315State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#50in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

80¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$50,412Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$14,442Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#25in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$31,329Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#26in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$41,090Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#36in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$76,407Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#47in the nation -

Wisconsin

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$39,955NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#35in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$60,724State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#24in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

77¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$53,239Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$14,447Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#24in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$33,883Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#16in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$46,448Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#13in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$89,651Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#29in the nation -

Wyoming

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$47,321NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2021-22, April 2023#12in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$60,819State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#23in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

91¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2023Minimum Living Wage

$57,705Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2020 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$18,748Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2021-22, NEA Rankings & Estimates, April 2023#14in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$31,963Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2021-22, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#25in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$41,154Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2020-21, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2023#35in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$89,741Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2021-22, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2023#28in the nation